Veterans didn’t have to pay Wally.

They had already paid enough he felt and since he had been one of them … in the trenches, he knew the premium price they had already paid for their country. He wasn’t going to add any financial woes upon their return to Canada and southern Saskatchewan.

“He never charged a veteran for his legal services,” said Charlotte Woodrow, the daughter of William Wallace Lynd … Wally Lynd as he will be remembered by the long-time residents of Estevan.

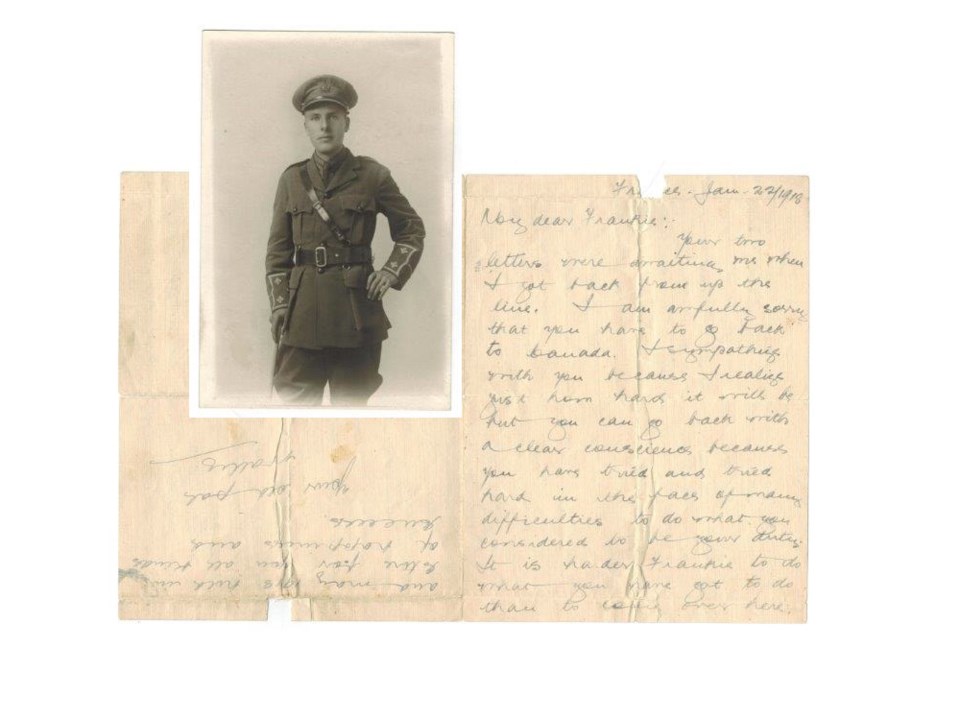

Lynd began his military career as a private in the early Canadian expedition forces with the 46th Infantry Battalion in 1914. Lynd, a former legal apprentice at the Brown, Wylie and Mundell law firm in Moosomin, later rose to the rank of lieutenant as the muddy, rat and disease infested trenches in France took their deadly toll if the German enemy troops, also imbedded in muddy ditches and bombed out potholes just a few metres away, hadn’t already extracted their toll.

It was a brutal war, that war that began 100 years ago. In fact, it was so devastating it was declared as the “war to end all wars,” because of its sad totality. Unfortunately, mankind has never been able to learn from its historical mistakes and 21 years later, flamed by the outrageous actions of a tyrannical dictator, Canadians and other allied armed men and women were required to march into a second great war. Since then, there have been others … different in scope, deployment and outcomes, but still armed combats that take lives too early and too brutally.

Wally Lynd, the kid who signed up in 1914, typified the type of character found in a lot of young people of the day. Born in Scalty, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland in 1891, Lynd moved with his parents and siblings to the Canadian prairies to farm, just outside Moosomin in 1906. The teenager and his two brothers and two sisters would hitch horses and plow a little land before heading off to school.

An office boy’s job in that Moosomin law firm, that paid $10 a month, brought him into the legal fold and the beginning of his matriculation exercises that would take five years to complete and would lead to a law student and apprenticeship status. That educational journey was interrupted by the First World War. Upon his return in 1918, Lynd completed one more year of studies, passed the bar exams, his daughter said, but never obtained a degree in law. In fact, he never passed through the doors of any university at any time in the process. But to all, including fellow lawyers, courtroom administrators and judges, he was “Lawyer Wally” with all the required status and certification, to satisfy the justice system.

Wally Lynd along with about 620,000 other Canadians put on a uniform. He never considered himself a hero for doing that. It was just what they needed to do to preserve democracy.

Lynd, in his southern Saskatchewan populated battalion paid steep prices on the battlefield. Some paid much more dearly than others.

The 46th I, bolstering the PPCLI infantry, for instance, fought for vital military positions at Fontaine-Notre-Dame for Britsh commanders. Three men earned Victoria Crosses for valour on that front as the Allied forces plowed slowly across the Canal du Nord, through the German lines at Raillencourt with men, “mowed down like grass,” said one post-battle report. The 46th Battalion, now joined by the 44th Battalion mainly comprised of men from New Brunswick, finally achieved their objective after a night of counter-attacks.

In one day, said historical writers, J.L. Granatstein and Desmond Morton (Canada and the Two World Wars), Canada lost 2,089 men, many of them hung up on barbed wire long enough to be shot and killed or wounded and drowning in mud.

Those, like Wally Lynd, wounded in the arm and shoulder by a machine gun blast, one month before the official end of that Great War, who survived those vicious battles, never needed reminding of the horrors of war.

And so, that’s why Wally Lynd didn’t charge World War veterans for his legal services in the aftermath. He had just been one of the 170,000 Canadians who had been wounded and considered himself to be very, very fortunate not to have been among the 60,000 Canadians who never did get home.

Wally Lynd is buried on Pender Island in British Columbia. A place he made home following his retirement from a long and distinguished legal career in Estevan.

His was a rich life, filled with wonderfully crazy friends and associates, a loving family, Irish humour and charm, a life in full that ended just short of his 101st birthday. But he always remembered … veterans had already paid their bill as far as he was concerned.

Lynd’s grave, marked with a shamrock, cross and the scales of justice, can be found on Pender Island. His great granddaughter Brielle, who honoured him this year with a prize winning Grade 11 composition, is joined by other family members in lighting and placing a candle of honour on that grave on November 11, just as we lay wreaths of honour in remembrance of those who served and didn’t make it home, and those who served, made it home, and have now placed the torch of freedom into our hands.

We will remember them.